The Point of No Return

A few months ago, shortly before the murder of Charlie Kirk, I stopped writing about Donald Trump and posting comments about his presidency and those in his administration on social media. This wasn’t because the subject has grown less urgent, or the President less problematic, but because the audience has calcified. I realized a few months ago that any endeavor to make my voice heard was fruitless. Anyone who disagrees with me already tunes me out within the first paragraph (if they even get that far), and the rest, the people who already agree with me, shake it off like another grim report indicating the end of times, nodding, then moving on with their day. It’s a surrender: the quiet acceptance that persuasion has become rare, and that argument itself can be a form of performance staged for two warring factions that no longer share a common language.

But lately I have felt that familiar, pit-in-my-stomach pressure rising again, not to win an argument, but to name what is happening as clearly as I can while it still matters.

I’ll be honest, what has drawn me back is personal. It’s the slow, bewildering realization that friends and family members I once respected, people I believed to be thoughtful, morally right, kind, and anchored in reality, have been absorbed into the cult of Trump. Let me point out that I do not use the word “cult” lightly or as an insult. I mean it in the sociological sense: a closed information system, a charismatic authority figure, an emotional identity fused to the leader, and a moral framework re-engineered so that loyalty becomes virtue and dissent becomes sin. (And, like most cult members, they don’t even know they’re in one.) I’ve been so convinced of the cult of Trump that not only have I made lawn signs and stickers stating the fact that MAGA is a cult, but people across the world have purchased them in droves. The brass tacks of all of this is that the people who frighten me most are not the professional grifters or the explicit authoritarians. It is the ordinary Americans, the ones who are either blind or willfully ignorant of what is in front of them, who have darkened my view of the country. And it’s sadly people whom I used to hold in high esteem, who watched a man stand at a podium and mock a disabled reporter and decided “that’s my guy.” (That they still follow him after all that’s come to light and all he’s done is something I don’t think I’ll ever truly understand.) And I don’t buy “he’s good for the economy” as an excuse either. He’s not, and no Republican president has created a successful economy since Eisenhower.

I do not know how we deprogram these people. I know it will require, at minimum, that they turn off Fox News and OAN, step back from algorithmic echo chambers, and the social media channels that play their fears like a fiddle, and return to a media diet that treats facts as constraints rather than suggestions. I realize this is not a small ask in 2026, when outrage is a business model and “engagement” is the currency of both politics and platforms. It is also a moral ask, because it requires humility: the willingness to admit you were manipulated. Often, I recommend people read AP News as a non-biased news source. It’s where I get 75% of my news, with the other 25% made up from a mix of the BBC, Fox News, and the Atlantic.

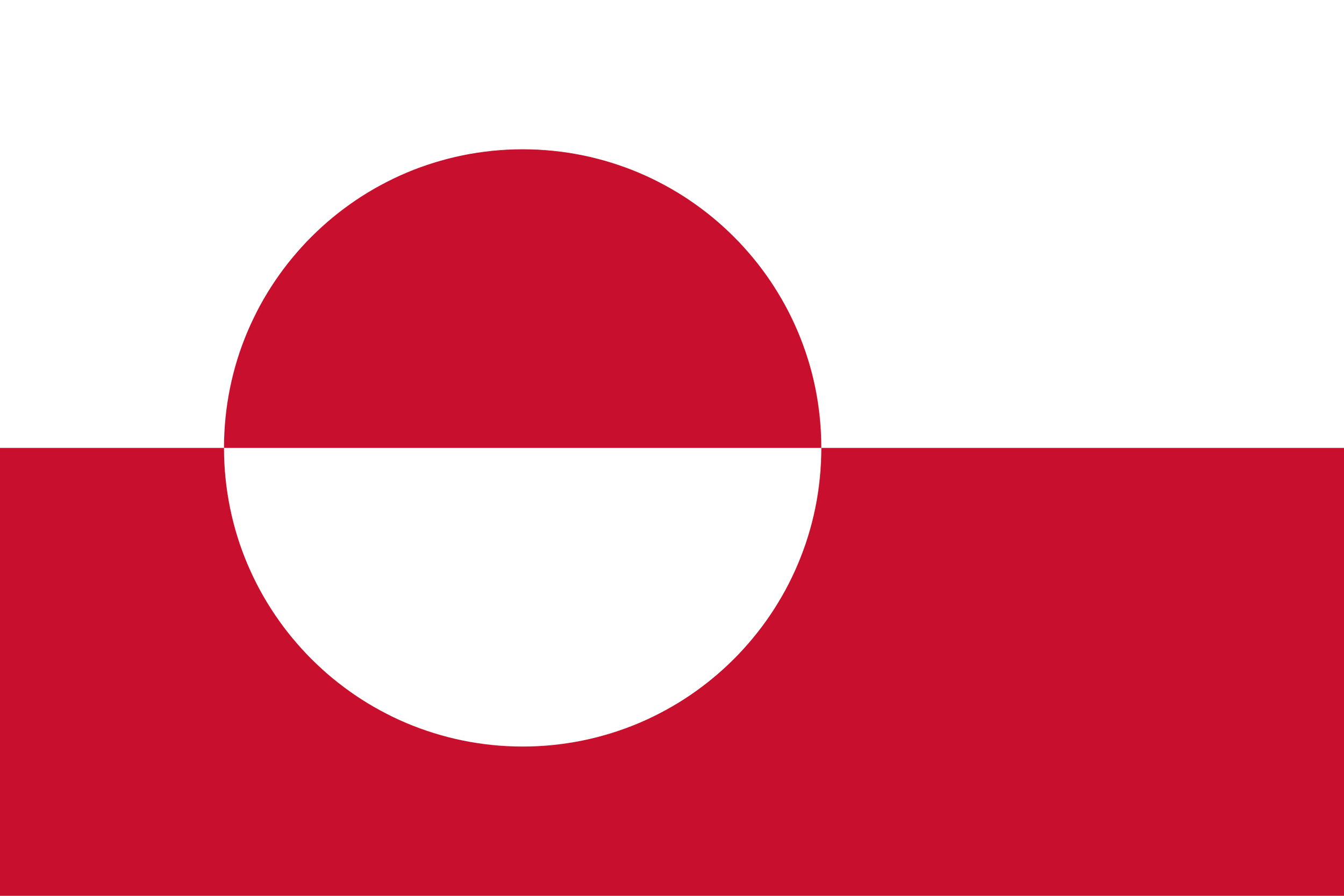

Let’s explore a hypothetical that feels less hypothetical with each passing week: Donald Trump choosing to take Greenland through the use of the United States Military. His administration’s renewed push to acquire Greenland has already precipitated a diplomatic crisis, and reports indicate that Denmark and Greenland have rejected the proposal as a violation of sovereignty, with European allies publicly bracing for escalation. A Reuters/Ipsos poll has shown Americans overwhelmingly oppose using military force to acquire Greenland, suggesting that even much of the public recognizes how dangerous this line of thinking is.

I am not arguing that Trump will do it. I am arguing that if he does, it would be the point of no return, not only for his presidency, but for America’s standing, credibility, and moral authority in the world. Further, I recognize that there’s a fear in certain circles that, if America doesn’t take over Greenland, China or Russia will. But I can’t disagree strongly enough. Greenland, a territory of Denmark, is part of NATO, as is the United States. Were Russia or China to attempt to take it, it would trigger a NATO response. It is a non-issue, and one designed to divert attention from the hard truths facing the Trump administration.

Greenland and the irreversible collapse of American legitimacy

The post 1945 international order has never been purely altruistic. It has reflected American interests and power unabashedly, and perhaps, with good reason. Post-WW2 America was a time of expansion, economic prosperity, and scientific achievement. But America also rested on a foundational promise: borders are not changed by conquest, and the threat or use of force against another state’s territorial integrity is illegal. That principle is embedded in Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter. This is reinforced by the UN General Assembly’s Declaration on Friendly Relations, which states explicitly that no territorial acquisition resulting from the threat or use of force shall be recognized as lawful.

If the United States violates that principle to seize Greenland, the damage is not merely reputational. It is structural. It’s fundamental. America would be affirming, through action, that the rules are not rules; they are tools, applied only when convenient. Every future American condemnation of aggression would become self-parody. Every lecture about sovereignty would sound like theater. The United States would be telling the world, without saying a word, that power is the only law.

The Greenland scenario is especially catastrophic because it implicates a NATO ally. Greenland is a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, and Denmark’s NATO membership extends to Greenland as part of that relationship. If the United States coerces or attacks a NATO member state to seize territory, the alliance’s credibility collapses. It becomes impossible to credibly insist that NATO is a defensive pact rooted in shared democratic norms when its dominant member behaves like a predator. One can even postulate that this is an act designed specifically to destabilize NATO, something Putin has wanted all along, and a move that would line up with other questionable moves Trump has made that benefit Putin.

That is why the Greenland fixation is not a sideshow. It is a stress test of the American identity we claim to embody.

And there is a haunting continuity here. This is not the first time Trump flirted with turning sovereign territory into a real estate transaction. In 2019, he seriously considered purchasing Greenland, and when Denmark’s prime minister called the notion absurd and reiterated that it was not for sale, Trump canceled a planned visit. What, in retrospect, appears as a bizarre episode of vanity now appears as an early symptom of something darker: a worldview in which sovereignty is negotiable if you are strong enough, and humiliation is justification for escalation.

Reading The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and the problem with the Hitler comparison

I am halfway through William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Currently, I am on the eve of Hitler’s invasion of Poland. And the striking similarities to the current United States are, to me, unmistakable.

It is trite to compare Trump to Hitler. It has been done so often and so lazily that it can feel like a rhetorical shortcut: a cheap escalation designed to end the conversation rather than deepen it. The comparison also risks flattening the distinct horrors of Nazi Germany into a generic symbol of evil. That is a real moral hazard.

And yet trite is not the same as wrong.

The similarity is not that Trump is Hitler, as a person, or that the United States is Nazi Germany, as a society. The similarity is in recognizable authoritarian mechanics: the deliberate weakening of shared reality, the delegitimization of independent institutions, the cult of the leader, the transformation of politics into an existential identity war, the substitution of spectacle for governance, and the use of targeted cruelty as both policy and signal.

You do not have to force the analogy. You can watch it unfold in real time: a narrative of national humiliation, a promise of restored greatness, enemies within, the press as enemy, courts and elections as rigged when inconvenient, loyalty as the measure of patriotism, and the idea that violence is regrettable but necessary to “take the country back.”

In Shirer’s account, the pre-invasion period is a lesson in how quickly “unthinkable” becomes “inevitable” once the public is conditioned to accept the leader’s framing of reality. Conquest is sold as self-defense. Aggression is sold as restoration. Neighboring sovereignty becomes a technicality. The world is told, in effect, that the strong may do what they will, and the weak must endure.

When I look at current reporting about Greenland, the administration’s rhetoric of force, and the normalization of annexation talk, I feel the same dreadful pattern: the gradual acclimatization to the morally impossible.

Stephen Miller, the ideology engine, and the danger of governance by impulse

One reason this moment feels so unstable is that Trump has always governed as an instrument of appetite: grievance, vanity, retaliation, and the need for attention. But appetite requires translation into policy, and that is where Stephen Miller enters.

Recent reporting has described Miller as a central force in translating Trump’s most incendiary impulses into actionable government machinery. In the worldview Miller has publicly articulated, international “niceties” are treated as signs of weakness, and politics is framed as a contest governed by strength and force. That posture is not merely rhetorical. It becomes a blueprint for how a superpower justifies doing whatever it wants.

It is tempting to describe Miller as Trump’s puppet master, the person pulling levers while Trump basks in the spotlight. Even if that formulation is overly neat, the underlying danger remains: a presidency in which the leader’s impulses are amplified by ideologues skilled at weaponizing the bureaucracy, unconstrained by prior guardrails.

The structure is what matters: a presidency increasingly defined by a small circle of hardline operators who regard democratic norms and international law as obstacles rather than commitments.

One nation under Trump, Minneapolis, and the selective use of “order.”

Authoritarianism often arrives wearing the mask of “law and order.” It does not reject state power. It reassigns it.

I find it amazing how bifurcated the country has been as protests erupted in Minneapolis after an ICE agent fatally shot Renee Good. Reporting describes the killing, the subsequent unrest, and President Trump’s threat to invoke the Insurrection Act to deploy troops to “put an end” to protests. This matters not only because it is a domestic crisis, but because it showcases the logic of selective repression: military force is threatened against protestors and cities framed as hostile, while the most direct assault on American constitutional order, the January 6 attack on the Capitol, was met with a delayed and contested security response and, ultimately, political minimization by Trump and his allies.

This is why the phrase “one nation under Trump” feels less like exaggeration and more like a diagnosis. The defining feature is not merely that he craves loyalty. It is that he uses the apparatus of the state to punish enemies, reward allies, and rewrite the boundary between legitimate dissent and illegitimate resistance.

The Insurrection Act itself is a dangerously broad tool, and legal analysts have argued that it is ripe for abuse precisely because it grants sweeping authority to deploy military force domestically with few constraints. In the hands of a leader who views opposition as treason, this is no longer a hypothetical concern. It is a plan.

The Christian contradiction

One of the most demoralizing features of Trumpism is how many of its most devoted adherents describe themselves as devout Christians while defending a leader who, in practice, embodies the antithesis of the teachings of Jesus.

The Christian tradition, at its moral center, emphasizes humility, repentance, truthfulness, care for the poor, welcome of the stranger, rejection of idolatry, and a suspicion of worldly power. Trump’s public posture is almost a perfect inversion: pride as virtue, cruelty as entertainment, lies as strategy, vengeance as strength, and personal glorification as the point. The gap is not subtle.

How do so many reconcile it? Partly by redefining Christianity as a tribal identity rather than an ethic, a flag rather than a discipline. Partly by convincing themselves that Trump is an imperfect vessel chosen for a holy purpose. And partly, I think, because propaganda has succeeded in training them to treat their enemies as existential threats, which makes any ally, no matter how morally repugnant, feel righteous.

This is why deprogramming is not merely informational. It is spiritual and psychological. It requires people to admit that they traded their professed values for the intoxication of belonging and the thrill of domination.

Distraction politics, Epstein, and the erosion of accountability

The logic of the Trump presidency has always included distraction as a form of governance. When a crisis or scandal looms, a new spectacle is generated, often designed to dominate the media cycle and force opponents to chase his chosen narrative.

Regarding the Epstein files, the public record is noisy, politicized, and susceptible to manipulation. Recent coverage notes that new releases include multiple mentions of Trump, while the Justice Department has also publicly characterized certain claims in the released material as unfounded and false. At the same time, reporting has described critics accusing Trump of trying to steer public attention away from Epstein-related scrutiny through unrelated provocations and culture war flare-ups.

The point is not to make a definitive claim about a motive that cannot be proven. The point is to observe a pattern: when accountability threatens, spectacle becomes a shield.

The same pattern appears in economic rhetoric. Inflation in the United States surged during the pandemic and then declined substantially from its 2022 peak, a trajectory that economists have analyzed as the result of multiple forces, including supply shocks and demand dynamics. In 2026, Trump’s public pressure campaign on the Federal Reserve and the political conflict surrounding monetary policy had itself become a major news story, with warnings from economists and commentators about the risks of undermining central bank independence. When governance becomes a perpetual campaign, economic policy becomes another stage for dominance and deflection.

Why Greenland is different, and why it would end us as we know ourselves

America has survived many disgraces. We have survived wars built on lies, torture justified as necessity, coups supported abroad, racial injustice at home, and the repeated betrayal of our stated ideals. We have survived because, however imperfectly, we have retained the ability to self-correct, and because our alliances and institutions have rested on at least a partial belief that America, when confronted with the truth, can be shamed into improvement.

A military seizure of Greenland would render that possibility moot.

It would tell the world that the United States is no longer even pretending to be a rule-bound power. It would collapse the moral distinction between America and the authoritarian regimes we claim to oppose. It would detonate NATO’s credibility. It would invite global instability by legitimizing conquest as normal. And it would make every future American appeal to international law ring hollow, because we would have demonstrated that we consider law binding only when we are not the ones violating it.

That is the point of no return.

What hope looks like now

Hope, in this moment, cannot be sentimental. It has to be institutional and courageous.

If those closest to Trump genuinely believe he is incapable of faithfully executing the duties of the office, the Constitution provides a mechanism for addressing this concern. The Twenty-Fifth Amendment, particularly Section 4, outlines a process for declaring presidential inability, with the vice president and a majority of the principal officers of the executive departments playing central roles, and Congress as the ultimate arbiter if contested. This is not a casual tool. It is an emergency brake. But emergency brakes exist for a reason.

More broadly, senators and representatives, regardless of party, must treat propaganda as a national security threat. A country cannot remain free if its citizens are trained to hate the truth. Media ecosystems that monetize delusion are not neutral marketplaces of ideas. They are engines of radicalization. The answer is not censorship. It is transparency, accountability, and a cultural recommitment to standards: evidence, correction, and the shared discipline of reality.

And for those of us who are not in the office, hope looks like refusing the temptation to give up on our neighbors. It means learning to speak across the divide without surrendering to it, to ask questions that reopen moral reflection, and to plant seeds that may not bloom immediately. Deprogramming is slow. It will require relationships, patience, and the steady offering of an alternative identity: an American patriotism not rooted in domination, but in the difficult work of pluralism and truth.

I am writing again about Trump, not because I think my words will convert the faithful, but because silence is a form of complicity. I am writing because I want a record that some of us saw the danger clearly, and that we tried, however imperfectly, to stop it before the worst became normal. I’m writing because I want my children to look back at this time and not ask me why I couldn’t have done more.

We can still choose a future in which America is not feared as an empire and pitied as a failed democracy. We can still choose a future in which our strength is measured not by what we can take, but by what we refuse to become.

The point of no return is not destiny. It is a decision.