Planetary Compute Commons

I consider myself an environmentalist. But I also co-founded an AI company, and those two hats don’t square very well. We can’t put the AI toothpaste back in the tube, but the strain on resources (mostly electricity and water) is already at scary levels. At Reflekta, we’re exploring offset options, such as tree planting. But that’s only a Band-Aid solution that doesn’t scale very well. What the AI and technology sectors need is not just offsetting, but a complete overhaul of how and where we utilize server farms, and what we do with their emissions.

The so-called “AI energy crisis” is not just a single bottleneck. It is a coupled system where model architecture, hardware efficiency, facility design, siting, and grid carbon intensity interact. It’s a backward and blunt approach: always build on compute, then scramble for power, cooling, and permits. A credible solution must change the shape of demand, not merely make cooling incrementally better.

So, here’s an idea I had. Call it a moonshot. Call it slightly insane. But there’s some validity to it, and it only requires someone with better engineering skills than me (so, most of the world), and those willing to upend the current tech paradigm to save the planet and, in the process, make AI even better.

I’m calling it Planetary Compute Commons. What it is, essentially, is a globally distributed compute network that treats the availability of clean energy in time and place as the primary scheduling variable. In practical terms, it combines modular “amphibious” data center nodes (some underwater, some terrestrial), liquid-based cooling, mandatory utilization of waste heat where feasible, and a software orchestrator that time-shifts flexible AI workloads to periods of renewable surplus and curtailment. The technical novelty is not any single component; it is the binding constraint: the system runs when the planet has spare clean energy and refuses to run when it does not, unless the workload is latency-critical.

There are a lot of big words in there. Most of them I had to look up. Some I credit thesaurus.com for introducing me to. So let’s break this down a bit more.

Why the conventional approach stalls

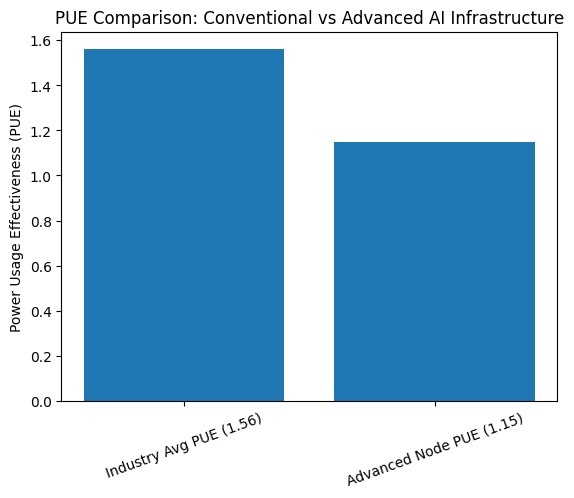

Industry average facility efficiency has flattened. Uptime Institute’s 2024 survey reports an average PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) of around 1.56, reflecting years of “low hanging fruit” already captured and a long tail of legacy facilities. PUE matters because it multiplies the total electricity required to deliver a given IT load. A 100 MW IT training cluster at PUE 1.56 draws roughly 156 MW at the meter, and a substantial share of that overhead is cooling, power delivery losses, and auxiliary systems. So really, we’re not spending energy on the data being created, but on all the things that make it possible to create data.

At the same time, the cost of building capacity is rising. Recent market reports place new data center construction costs in the $8 million to $12 million per MW of IT load range, with AI-optimized facilities sometimes higher due to electrical and mechanical complexity. At 100 MW of IT load, that implies $0.8 billion to $1.2 billion for a “typical” build, and potentially materially more for high-density AI campuses. In other words, this is not a problem that scales by brute force without hitting severe capital, grid, and permitting limits.

The moonshot thesis makes time a first-class resource

Planetary Compute Commons rests on a simple but underused distinction: not all AI work is equally time sensitive.

Real-time inference must run now, near users and applications.

Flexible workloads (fine-tuning, evaluation, batch analytics) can tolerate hours-long delays.

Opportunistic workloads (such as many forms of training, synthetic data generation, and large-batch experimentation) can tolerate days, so long as throughput is guaranteed.

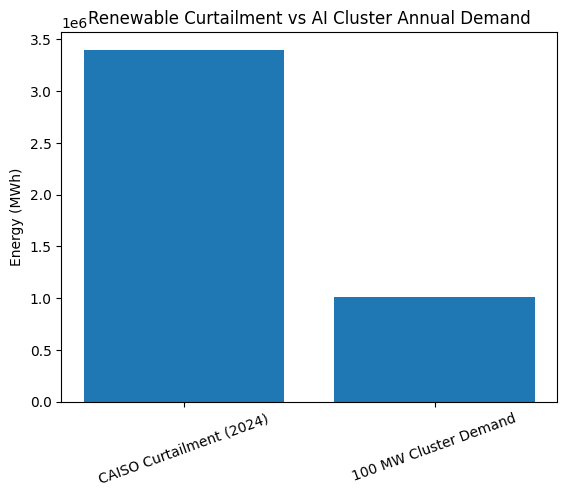

My idea is to force categories 2 and 3 to run primarily on surplus clean energy that would otherwise be curtailed, spilled, or priced near zero, and to run them in regions where electricity is low-carbon and abundant. Curtailment is not theoretical. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reports that CAISO curtailed 3.4 million MWh of utility-scale wind and solar in 2024, a 29% increase from 2023, largely due to springtime oversupply. Independent analysis also points to multi-terawatt-hour curtailment in other markets, such as ERCOT, in 2024, driven by congestion and rapid renewable buildout.

Here’s an example: a 100 MW cluster running continuously consumes about 876,000 MWh per year. CAISO’s 2024 curtailment alone could power roughly four such 100 MW clusters for a year if the energy were fully capturable and deliverable, which in practice requires transmission, co-location, or storage, but it shows the order of magnitude.

This is where the key part of Planetary Compute Commons comes into focus as the conductor of the symphony. Essentially, it’s a scheduling layer that ingests grid conditions, marginal emissions, local prices, curtailment forecasts, and node thermal constraints, then allocates queued workloads across geography and time. The product promise is not “cheaper compute” alone, but compute with a verifiable carbon and water envelope.

Amphibious nodes, underwater and far north, but only where they pencil

The concept uses two physical node families. (Yes, I’m using the term “node” because it sounds scientific. But if you’re more comfortable with the terms “junction” or “for,k” feel free to replace those below.)

A. Terrestrial surplus nodes near clean, firm generation and grid capacity.

These are sited in areas with accessible power, low-carbon, hydro-heavy regions, geothermal corridors, wind buildouts with persistent curtailment, and industrial zones with district heating potential. Canada can be attractive in parts precisely because some regions have abundant low-emission electricity, but the “far north” is only compelling if grid connections and fiber are already in place. I also feel Iceland is a fantastic location for these nodes, as it’s incredibly windy and cold and has a robust carbon-neutral electric grid throughout most of the island. These remote sites that rely on local fossil generation can negate the emissions rationale.

B. Underwater or coastal nodes where seawater cooling and land scarcity change the economics.

Underwater data centers are feasible and have been demonstrated. Microsoft’s Project Natick reported markedly improved reliability in its sealed underwater environment, with the underwater server failure rate one-eighth that of a comparable land-based control group. More recently, a commercial-scale undersea project off Shanghai has been reported at roughly RMB 1.6 billion (about $226 million), with plans to scale to tens of megawatts and a reported target PUE of around 1.15, though independent validation at scale remains an open question.

Underwater nodes are therefore not science fiction, but they are not a universal solution. Their trade-offs are straightforward: cooling efficiency and potentially fast modular deployment versus harder maintenance and retrieval, corrosion and sealing challenges, and ecological scrutiny of thermal discharge. I feel like the best option with these is to treat underwater modules as one tool in a diversified fleet, particularly for coastal inference and for flexible workloads where latency is not critical, and where permitting and physical constraints make land builds undesirable.

Liquid cooling and the efficiency wedge: how savings show up

On the facility side, liquid cooling, whether direct-to-chip or immersion, addresses the rising heat flux of modern accelerators and can reduce reliance on evaporative cooling and large air-handling systems. A Vertiv analysis reports that introducing liquid cooling in a fully optimized study yielded a 10.2% reduction in total data center power and improved efficiency metrics compared with air cooling, though results vary by design and baseline. Policy and technical overviews similarly note that direct-to-chip and immersion approaches can reduce both energy and water use relative to conventional cooling.

A better way to show this is via PUE improvement. Let’s say a site moves from the industry average of 1.56 to 1.15, a level reported as plausible in certain advanced builds and referenced for at least one undersea project, the arithmetic is substantial.

For a 100 MW IT load:

At PUE 1.56, total draw is 156 MW.

At PUE 1.15, total draw is 115 MW.

That is a 41 MW reduction at the meter, about 359,160 MWh per year.

At electricity prices of $50 to $100 per MWh, the annual operating savings from that PUE delta alone are roughly $18 million to $36 million per year, before accounting for water savings, reduced chiller capital, or density-related real estate effects. Obviously, actual prices and savings depend heavily on contracts, peak pricing exposure, and local rate design, but the magnitude is real.

Waste heat as a requirement, not a nice-to-have

Most of the electricity consumed by AI ultimately becomes low-grade heat. Converting that heat into a valuable product is difficult but not impossible, particularly in cold climates with district heating, greenhouses, or industrial processes that can use moderate temperatures with heat pump boosting. The academic literature has increasingly focused on techno-economic integration of data center waste heat into district heating networks, highlighting both the opportunity and the dependence on local heat demand, infrastructure proximity, and temperature requirements.

With Planetary Compute Commons, I’d like to make a strong claim: terrestrial nodes near population centers must either export heat or justify why heat export is infeasible. This shifts permitting and community relations, because the data center is no longer only a strain on resources; it becomes a contributor to local energy services.

Based on their locations, underwater nodes will generally not be able to deliver heat to district loops, so they must instead meet strict thermal impact criteria and, where possible, pair with processes such as localized desalination or other thermally driven functions. I must admit, however, that this is currently more speculative and site-dependent than district heating reuse.

Cost structure, capex, opex, and what changes

Let’s get down to business.

Baseline capex

With published ranges of $8 million to $12 million per MW for many data centers, and higher for AI-dense builds, a 100 MW terrestrial node is often a billion-dollar-class asset. Publicly reported undersea projects, such as the one in Shanghai, suggest that undersea capital can also land in a similar “millions per MW” regime, at least on paper, although comparisons are tricky because public figures can bundle offshore wind, subsea infrastructure, and phased capacity.

Opex levers

The largest recurring line items are electricity and, depending on design, cooling-related power and water. Reducing PUE from 1.56 to 1.15 creates the electricity savings I mentioned above and can also reduce exposure to constrained water resources by displacing evaporative cooling.

System-level savings from time shifting

The orchestrator can capture two additional value streams beyond PUE.

Energy cost arbitrage and curtailed energy offtake

Running the highest potential workloads during surplus periods can lower average energy costs, especially in markets that experience negative or near-zero pricing during renewable oversupply. Even when prices are not negative, absorbing energy that would otherwise be curtailed can be contracted at favorable rates for both parties, though feasibility depends on interconnection and local congestion.Deferred grid upgrades and improved social license

If compute behaves like a flexible load, it can reduce peak strain rather than amplify it, which can change interconnection outcomes and permitting. This is harder to value in a simple spreadsheet, but it can help decide whether a project is buildable at all.

Underwater versus far north Canada, where each fits in the idea

As I mentioned above, underwater data farms are best viewed as a specialized node type: high cooling efficiency, minimal land use, potentially strong reliability in sealed environments, and proximity to coastal demand. The evidence base remains relatively narrow, but Project Natick provides a strong demonstration, and the new wave of reported commercial projects suggests growing interest. Their weak points are maintenance, logistics for retrieval, and unclear environmental impact factors.

Far north Canada, by contrast, should not be pursued primarily for cold air. Cold helps, but power delivery and fiber diversity decide viability. The right Canadian strategy is usually “clean power rich, infrastructure connected” rather than “as far north as possible.” When those conditions hold, a cold climate can improve free cooling hours and support heat reuse economics, but this whole idea does not depend on latitude, it depends on the ability to bind compute to low carbon availability.

What success looks like, and what would convince a skeptical committee

Primary success metrics

Verified marginal emissions per training run and per inference token.

PUE and water usage effectiveness performance at sustained high density.

Utilization, measured as achieved compute per installed GPU, not just nameplate capacity.

Community impact, quantified via heat delivered or fossil heat displaced for terrestrial nodes.

Pilot roadmap

A 5 to 10 MW terrestrial surplus node co-located at a curtailment-heavy renewable site, running only flexible and opportunistic workloads, proving that scheduling can absorb surplus without harming reliability.

A coastal module, potentially underwater or shore adjacent, providing PUE improvements, low water consumption, and retrieval-based operations.

The Planetary Orchestrator, the software layer that converts grid and climate signals into workload placement decisions, with auditable reporting.

To sum it all up, yes, Planetary Compute Commons is a long shot because it redefines AI infrastructure as adaptive, not always on, and because it treats time shifting, heat utilization, and ecological constraints as first-order design inputs rather than externalities. Underwater data farms and northern siting are valuable tools. Still, they are subordinate to the larger insight: the cleanest, cheapest kilowatt hour is often the one the grid cannot use at that moment. If AI can learn to wait and its infrastructure can move, then the “energy crisis” becomes less of a brick wall and more of a scheduling problem with large, tractable payoffs.